Cartooning has become eternally linked in our collective imagination with childhood, Disney movies, and frivolousness. At the same time, no other art form has been so consistently intertwined with US political life. Over the next few posts, I will be paying tribute to this most political art, and the many ways that it has intersected with politics and social change.

The word “cartoon” — originally referring to the preparatory drawings for Italian frescoes — came to be used in London in the 1840’s to refer to humorous, and often political, drawings printed in magazines and newspapers (Harvey, 2009). Nowadays the term “cartooning” has broken free of any one particular form, referring as well to art that shares a set of conventions such as thick, black outlines and the use of caricature and symbol.

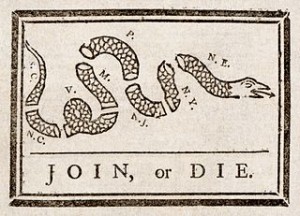

Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1754

The art of political cartooning in the US dates back to at least 1754, when Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette printed his “Join or Die” woodcut advocating unity among the states. Now it is a fixture of political magazines and editorial pages across the country, and it has been given new life online where such cartoons proliferate wildly.

Meanwhile, cartooning took another step towards becoming a staple in our lives in the late 19th century — this time in color. The Funny Pages were born along with the color printing press, and in the early 20th century were popularized by major newspaper publishers like William Hearst. The wall between the funny pages and the news has always been porous, with titles like Doonesbury and the Boondocks taking on the political establishment, and often making there way to the editorial pages.

The Boondocks, by Aaron McGruder

The next logical leap forward was the comic book, extending cartooning into long-form storytelling. Comics, like their strip-based forebears, were cheap, targeted at children, and largely seen as disposable. But as a popular art form, comics were both barometers of the times and players in the political game. Superheroes, for example, have served as working-class heroes, pro-war patriots, and cultural critics (Morrison, 2011). A rich, underground comics scene erupted as well, serving as a visual language for the growing counter-culture.

Today comics — along with their elder siblings the “graphic novels” and their more popular Japanese cousin, manga — are reaching into ever-new arenas. Now we have comic journalism, comic history, comic-based curriculum materials. The web has given comics and cartoons new, interactive elements. Cartooning is more relevant than ever.

Visit in the coming days for more on cartooning, the “most political art.”

Harvey, R. C. (2009). How Comics Came to Be. In J. Heer & K. Worcester, A comics studies reader. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Morrison, G. (2011). Supergods: What masked vigilantes, miraculous mutants, and a sun god from Smallville can teach us about being human. New York: Spiegel & Grau.

2 thoughts on “The Most Political Art”

Comments are closed.