This is part 5 in an ongoing series about art

and power

I’ve been reading and writing a lot about power, looking at some of the big power theories out there. But many of our everyday theories of power are not buried in academic libraries, but right in front of us in gleaming spandex. I’m talking about superheroes. If superhero comics are all about power, what kind of power are they talking about? What are they teaching us? Read on, true believer!

Power as the Ability to Act

Power as the Ability to Act

Since Superman’s first appearance in Action Comics, most superheroes have been defined

by one or more powers: flight, invisibility, healing factor, vomiting,

etc. In this sense, a power is an ability. This usage implies that we all have

“powers,” though ours are decidedly less super. I, myself have the power to walk, to

breathe, to protest, and to blog. In their typology of power, Lisa VeneKlasen and Valerie Miller would call this kind of

power “Power To…the unique potential of every person to shape his or her life

and world.” This use of the word power also assumes that power is something that an

individual has and can use — though it can be taken away with some

well-placed kryptonite.

Some community organizers, like Ernie Cortez Jr. of the IAF, speak about power in a similar way. Because they see building power in marginalized communities as positive, they separate the word power from negative ideas like oppression and domination. They often point out that power in Spanish — poder — simply means “to be able to.”

Power = Responsibility

Power = Responsibility

Perhaps the most famous line in comic book history came from Spiderman: “With great

power comes…great responsibility!” Superheroes are those who take up this mantle of

responsibility to others, while supervillains do not.

This resonates with the ideas of Steven Lukes. Lukes says that one of the reasons we need to talk about power is because we need to figure out who we can hold responsible. He defines the “powerful” as those to whom we can attribute responsibility — either for acting, or for not acting. Just like Spiderman holds himself responsible for not stopping a thief, who later killed his uncle, we can hold powerful people like CEOs and politicians responsible for not protecting the environment (for example) even if they aren’t the ones doing the polluting. This is because they have the power (and thus the responsibility) to step in.

Power Corrupts

Power Corrupts

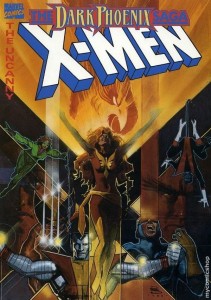

In one of my personal favorite comic book stories of all time, the Dark Phoenix Saga,

the author (mis)quotes Lord Acton: “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts

absolutely.” We see this corruption in action as Phoenix, who has the power to consume

stars, turns into Dark Phoenix and does just that. In a more recent twist on this theme,

the comic series Irredeemable shows how a superman-like character, with a bit of

an inferiority complex, transforms into an unstoppable villain.

Today the casualness with which we approach corruption in government shows that we pretty much take this idea as a given. The “balance of powers” in governments like the US is an attempts to avoid absolute power and thus absolute corruption (though this balance seems to be deteriorating).

Money is Power

The X-men got their powers from genetic

mutation, Superman from our yellow sun, and the Fantastic Four from “cosmic rays.” But

Batman was just really, really rich (and a little crazy). This was enough to land him a

spot among the worlds most powerful superheroes in the Justice League.

The X-men got their powers from genetic

mutation, Superman from our yellow sun, and the Fantastic Four from “cosmic rays.” But

Batman was just really, really rich (and a little crazy). This was enough to land him a

spot among the worlds most powerful superheroes in the Justice League.

In his classic, much reprinted book “Who Rules America,” G. William Domhoff has thoroughly documented the connection between economic wealth and power over the history of the US. He doesn’t quite say money is power, but shows that money is a resource for power, money can lead to power, and money is an indicator of where power lies — showing us just how unequal power distribution is. We now know people like Bruce Wayne as “the 1%.”

Collective Power

Collective Power

While many comics celebrate purely individual power, there is also a strain of

collective power running through the superhero world. The X-men in particular

continually learn that while each has a specific, individual power, its usually only by

combining their powers that they can succeed. As the recent Avengers movie showed, even

the most powerful must unite when the big threats come down. Combining our powers makes

us more than the sum of our parts.

The power of collective action is sometimes called “power with.” Bernard Loomer writes about a similar concept of “relational power,” which is the power that comes from true collaboration, from not only being able to change others but being open to change yourself.

What Comics Don’t Teach Us About Power

While there are many types of power at work in superhero comics, it is perhaps more

notable which types of power are absent. There is little to no talk of the power of

systems and institutions, or the power of cultural forces like mass media. What if power

is not something a person can “have” at all, but something that surrounds all of us,

shaping not only what we can do but what we even think is possible? I’ll be exploring

some of these ideas in upcoming posts in this ongoing series.

“The decision to act heroically is a

choice that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in time.”

“The decision to act heroically is a

choice that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in time.”