Can rituals — with all their focus on continuity and tradition — be a force for social change?

Last week, about fifteen family members and friends gathered in a small chapel in Detroit for my grandfather’s funeral. The dais was decorated with white flowers and photographs of Papa Joe at various points in his 93 years — a young navy man in a bomber jacket, an excited groom, a proud father with his three girls, the grandfatherly face I remember best. The funeral was a catholic mass, complete with responsive readings, bible verses, and communion. Then two representatives of the Navy played taps, and performed a flag folding ceremony, honoring Papa Joe’s service during WWII. These rituals, each movement prescribed down to the creasing of the flag, had a surprisingly strong effect on me. At one moment, during the playing of taps, I was able to imagine my grandfather as a young navy man hearing those same notes decades earlier.

The experience has left me thinking a lot about rituals. According to the sociologist Robert Wuthnow rituals are any actions or events that have symbolic meaning beyond their instrumental value. For the navy, folding the American flag is not just about easy storage. And rituals communicate something about the social order: its norms, power relations, etc. We are surrounded by mundane rituals every day — from sending thank you cards to brushing our teeth. But there is a special place in our lives for large, collective rituals that we share with our communities.

Rituals are often associated with maintaining the status quo. They are about continuity. Their repetition and lack of change are what make them powerful. Rituals are used to inculcate new members into a culture, or affirm a group’s values. But can they also be forces for change and resistance? Organizers and cultural workers are doing just that, in a few different ways.

Northwest Bronx Annual Meeting

Rituals as Unifying Practices

Many organizing groups and social movements have made use of the rituals of religion to

cohere participants together. In the research my colleagues and I conducted with the Northwest Bronx

Community and Clergy Coalition in NYC, religious ritual was key to developing a

sense of “shared fate” among the diverse Bronx population. For example, beginning their

annual meeting with Christian, Muslim, and Jewish prayers served to connect members to the

social justice values inherent in their own faiths, and to affirm shared values across

religions.

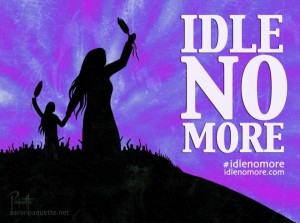

Rituals as Counter-Narratives

While many rituals serve as connections to the

past, this does not always make them conservative. Last

post I wrote about the Idle No More movement, whose public actions in support of

indigenous sovereignty are built around the traditional native circle dance. In a society

that often treats indigenous culture as something for the history books, these rituals help

to reassert the strength of a marginalized culture. Moreover, doing so in a mall contrasts a native ritual of unity with one of

the key rituals of consumer culture — shopping.

While many rituals serve as connections to the

past, this does not always make them conservative. Last

post I wrote about the Idle No More movement, whose public actions in support of

indigenous sovereignty are built around the traditional native circle dance. In a society

that often treats indigenous culture as something for the history books, these rituals help

to reassert the strength of a marginalized culture. Moreover, doing so in a mall contrasts a native ritual of unity with one of

the key rituals of consumer culture — shopping.

New Rituals for a New Culture

Often citing Gandhi’s call to “be the change you want to see in the world,” social change

groups develop internal cultures where they can live out the values they preach. One way to

do this is through creating or adapting new rituals that embody these new ways of being. The human megaphone or

people’s mic used by Occupy Wall Street protesters was more than just a clever

solution to restrictions on sound equipment. It became a ritual through which the group

publicly lived their values of do-it-yourself sufficiency and collectivity.

Toolbox of Activist Rituals

Over the years, an array of rituals have been created specific to activism and social

change. Once innovative, these rituals now serve as available and adaptable resources:

sit-ins, work stoppages, marches. They link one action to the history of activism and the

spirit of social change. The modern community organizing movement has similarly developed a

set of shared rituals, such as one-on-ones, narratives of empowerment, and public

meetings (Hart,

2001).

SOA Watch March

Rituals and Emotion

Finally, rituals can elicit and make space for emotion, a powerful driver for involvement in

social action (Taylor & Whittier, 1995). SOA Watch, a group that protests the US

government training of military personnel from Latin America, gathers each year outside Fort

Benning in Georgia for a massive march/vigil. Each participant holds a white cross with the

name of someone killed by soldiers trained at Fort Benning. Leaders read off a long list of

the dead, followed by a chorus of “presente” (present). To be a part of this march is to

feel a combination of sadness and anger, and to recommit oneself to the cause.