Last week I had the privilege of talking to a powerful cultural organizer from Oakland. Favianna Rodriguez is a visual artist best known for her political prints and posters addressing issues from the Iraq war to women’s rights. She is the director of CultureStrike, a grassroots collective of artists, and the founder of Presente.org, an online network “dedicated to the political empowerment of Latino communities.” She has recently been featured in an online documentary titled Migration is Beautiful.

We began by talking a bit about how Favianna came to her artistic and political work, but quickly fell into discussing the role of artists in the immigrant rights movement, the challenges political artists face, and the difference between art as a tactic and art as a strategy for social change. We also spoke about her effort to promote the monarch butterfly as a powerful symbol of the humanity and beauty of migrants.

How did you first get involved with art, when did that start?

Since I was a child I

was really into art, but it wasn’t something that was encouraged in my

family. My family wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer; given I was a first

generation college student it was always really important for me to pursue,

in their eyes, a more meaningful career. But art has always been a way for

me to claim my identity and make sense of who I was, because I grew up in an

environment where I would be one of the only students of color in many

honors classes in high school. I would find myself not reflected in the

curriculum, not reflected in student government or extracurricular

activities, so for me art was a way to claim that space.

Since I was a child I

was really into art, but it wasn’t something that was encouraged in my

family. My family wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer; given I was a first

generation college student it was always really important for me to pursue,

in their eyes, a more meaningful career. But art has always been a way for

me to claim my identity and make sense of who I was, because I grew up in an

environment where I would be one of the only students of color in many

honors classes in high school. I would find myself not reflected in the

curriculum, not reflected in student government or extracurricular

activities, so for me art was a way to claim that space.

When did politics and activism start to move into the picture?

When I was 16 the governor of California introduced Proposition 187, the first anti-immigrant state based proposition. Around that time you also saw propositions killing affirmative action; you saw the prison industrial complex creep up in California via Proposition 21, which was a way to criminalize young people of color. All of that happened in my teenage years and I found youth organizing. I got involved when I was about 14 years old, walking out of my high school, doing actions at the juvenile detention centers. For me organizing was a real wakeup call because I could really understand how political power was formed.

Back then were you finding ways to work your art into your organizing?

Yeah, I was more working in my art as a designer. I was filling the need that was emerging, which was that you needed flyers, you needed educational materials for the community. I understood art as a tactical thing, and not necessarily as a strategy.

What does it mean for art to be a tactic instead of a strategy?

For a long time I was using my art skills to serve the immediate and short term needs of movement work, whether that would be making flyers or giving away art for auctions by political organizations or doing pop-up art exhibits at rallies. On the other hand, I would spend time developing my own body of work, or working with other artists. And we were not necessarily thinking about policy outcomes or the next rally — we were thinking, “What is this space of big ideas we want to go into? What are the values we want to promote?” I began to understand that while artists were valued for the short-term work that they can do, we were not valued for the creative capacity to touch people’s hearts. Dance choreography, or a short play, or a novel — anything that did not fit into the short-term needs of a movement, people just could not see it as useful.

Now I see the value of cultural strategy, which means to me that we are thinking about culture as a tool that can move our ideas forward. Culture is a space that we actively need to be working in, and we need to respect the labor of artists. Its important to work in a rapid response mechanism, but its equally as important to work on long term ideas that are going to shift the way people fundamentally think about an issue. Cultural strategy is not communication strategy, and art is not just as a tactic. When you see artists as a tactic it means you have predesigned a pathway to a campaign which the artist is going to participate in. To me cultural organizing is to see that art it can be a complimentary path that is not driven by the short-term needs of a campaign. Another part of cultural strategy is artists also need to be organized.

What does that look like when artists are organized?

When artists are organized, it means we have an awareness of the political strategy, and the general direction the movement is trying to go in, so that we can position ourselves. This is why I think it’s important to use the word strategy. I do think we need to be strategic with our timing. We have to think about how our art is going to advance or not advance different beliefs.

What do you see as the ideal relationship between artists and more traditional organizers?

I think that there has to be ongoing communication. Artists are not sitting at the table when strategy is being designed, and I think that’s a mistake. Artists need to be a part of overall movement work in a way that really values what we do. The tendency has been to contact artists at the end, about campaign engagement, or “Now that we have our rally planned, let’s invite the artist.” That to me is only one very small piece of cultural strategy.

Also, artists need to have strong relationships with movement folks so we can understand what they’re pushing for, because some things we do could actually not help. I’ll give you an example. Steve Jobs’ widow just released a video-based site called The Dream Is Now, and its all about undocumented youth. I can tell you, as somebody who works directly with undocumented youth and has good relationships with organizers, that the dream narrative is no longer as helpful to our movement as it was 2 years ago. Undocumented youth are now saying “It’s not just about us as youth, we want our parents legalized. Our parents brought us here because they are responsible and they want opportunity for us, and we’re not going to shove our parents under the bus.” At CultureStrike I work with artists, and if artists say we want to do something around young DREAMers I’m able to say “Well, the political strategy is no longer moving in that direction. In fact, dreamers have gotten some relief via DACA. What is now urgent is that we address the deportation of parents, and move away from a youth-only lens” And by understanding where the movement is at it makes the art all that more powerful and effective.

What are the different roles arts are playing, or could play, in the immigrant rights movement?

I’ll give you a great example. A group of eight senators introduced what they call a blueprint for comprehensive immigration reform. That blueprint included drones at the border and at least two decades of waiting for citizenship. Unless you understand the nuances of what this means, the public hears the words “comprehensive immigration reform,” and may not necessarily approach with a critical lens. Here’s where artists can come in really great: artists can expose the truth about these policies and highlight the information or misinformation in a way that simplifies the message. We can begin to emphasize what drones are, connect it to the immense amount of debt, saying “This is what border enforcement looks like, this is what border enforcement costs.”

At the same time, there are 11 million undocumented migrants. How do we as artists help people see what those 11 million look like? It’s children, it’s mothers, it’s parents, it’s students it’s workers. How do we humanize that so that it’s not just a figure, so it tells a story?

We are all hoping that this is the year for immigration reform, and you can expect there to be a lot of rallies and visits to congress and marches. This is what we’ve been doing for the last six years already. What would new kinds of cultural engagement look like so we are not just repeating the same way of telling the story? Theatrical pieces, mobile art labs, filmmakers, concerts all over the country. What about Comic books, graphic novels, street art highlighting the immense pain that so many children feel from losing a parent because they are being deported.

Maybe you could talk about the symbol of the Butterfly, and what you’re trying to do with that.

The immigrant rights

movement began to slowly adopt the butterfly as a symbol. As an artist, and

as someone who studies symbols like the pink triangle, the black power fist,

the black panther — I think symbols definitely have the ability to create a

culture of resistance. So for me it was important to popularize the image of

a butterfly. I wanted to piggyback on the symbol of the butterfly as a

visionary symbol. Butterflies can cross borders, so the butterfly is the

symbol to talk about the beauty of migrants as they are moving from place to

place. Just like butterflies migrate in order to survive, people migrate in

order to survive. It is not just about economics, it is also about people

wanting to be unified with their families, or people wanting to be safe from

environments where they can’t be gay, or women escaping situations that are

dangerous to them, or young people trying to find opportunities. These are

all beautiful stories of who we are as humans, and I think that the

butterfly is very symbolic of that.

The immigrant rights

movement began to slowly adopt the butterfly as a symbol. As an artist, and

as someone who studies symbols like the pink triangle, the black power fist,

the black panther — I think symbols definitely have the ability to create a

culture of resistance. So for me it was important to popularize the image of

a butterfly. I wanted to piggyback on the symbol of the butterfly as a

visionary symbol. Butterflies can cross borders, so the butterfly is the

symbol to talk about the beauty of migrants as they are moving from place to

place. Just like butterflies migrate in order to survive, people migrate in

order to survive. It is not just about economics, it is also about people

wanting to be unified with their families, or people wanting to be safe from

environments where they can’t be gay, or women escaping situations that are

dangerous to them, or young people trying to find opportunities. These are

all beautiful stories of who we are as humans, and I think that the

butterfly is very symbolic of that.

The butterfly as a symbol of policy can be a little bit tricky, because the butterfly clearly crosses borders . Yet I don’t believe in our lifetime we are going to see open borders. However, I think it’s an important idea to push out, because art sometimes is about imagining what could be, it’s about allowing people to think really big. Even though it may not translate to a policy outcome just yet, its important for the idea to be there because people in their subconscious associate migrants with really ugly concepts. People associate migrants with leeches, or they think about migrants like “Those migrants don’t belong here, they’re taking my job.” And that is because the media has repetitively shown those symbols, so we need to counter those with more positive symbols.

Who else do you see in the immigrant rights movement, or other movements, that you particularly think is doing great work around cultural organizing?

I think that 350.org does an excellent fob of activating folks around climate change. A few years back they did something called EARTH where they organized, in cities around the world, huge art productions that you could only see via satellite all produced on a particular day. I thought that was really powerful because first, it really maximized on artists being problem solvers. At the same time it requires community participation, because you needed people out there to make it work. And also it centered on a really simple idea, the number 350.

What keeps you going in this work?

I wake up and I am just

so excited that my job is to think about how to organize artists. For a long

time as an artist I felt really frustrated about the way artists’ labor

wasn’t recognized, and frustrated because the art word marginalizes artists

of color and socially engaged artists. The art world is already such an

ultra-capitalist environment and sometimes that’s all we’re offered, that is

shown to us as the ideal. So to be able to say to my fellow artists, “Lets

get organized, lets think about the work that we do, and also think

differently about art overall. There’s a saying that says “art workers don’t

kiss ass,” and that is so true. The awesome thing about being an artist is

that we have space to do the most controversial, in-your-face content that

you can imagine and we can totally get away with it because we’re artists.

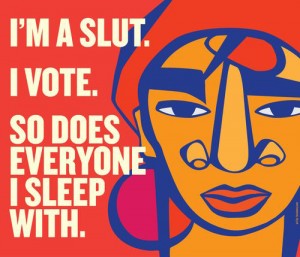

That drives me. You’ve seen my “I’m a Slut” poster — I would never get the

support to do that through the nonprofit world, and yet its so needed.

I wake up and I am just

so excited that my job is to think about how to organize artists. For a long

time as an artist I felt really frustrated about the way artists’ labor

wasn’t recognized, and frustrated because the art word marginalizes artists

of color and socially engaged artists. The art world is already such an

ultra-capitalist environment and sometimes that’s all we’re offered, that is

shown to us as the ideal. So to be able to say to my fellow artists, “Lets

get organized, lets think about the work that we do, and also think

differently about art overall. There’s a saying that says “art workers don’t

kiss ass,” and that is so true. The awesome thing about being an artist is

that we have space to do the most controversial, in-your-face content that

you can imagine and we can totally get away with it because we’re artists.

That drives me. You’ve seen my “I’m a Slut” poster — I would never get the

support to do that through the nonprofit world, and yet its so needed.

Hola! Como esta? Espero se acuerde de mi en el evento hace quince dias…Raquel Martinez .Yo estaba en la mesa de RAP como voluntaria. Te boy a platicar un poco del otro grupo separado al que pertenezco de Mujeres Latinas, aqui tenemos muchas limitantes porque no hablamos un buen Ingles y no podemos conectarnos con los jefes de los oficiales de policia que continuamente cometen acuso de autoridad, racismo, discriminacion….. Otra limitante es que aun no nos registramos como organizacion y necesitamos asesoria para hacer una pagina en Internet………

Mi historia personal tiene muchos abusos de autoridades, de ciudadanos miembros de la Familia de mi ex-pareja, y si le interes se la podria profundizar mas en otro e-mail.

I am part of a group of Latin Women in Colorado Against Domestica Violence and Witness crimes that have come out of the violence at home, other cases are extreme because they already left the control of the abuser and continuous because relatives of the abuser are involved her family… Contact to UD to see if there is an idea of storytelling so that the legal system will know more I emotional damage to a victma that edge to defend itself or the abuser makes use of his family to staking, intimidate, …and where the authorities do not prevent the danger and that sometimes the police arrested to the victim when he/ she defends. We have cases of total negligence of the authorities, other cases reflect racism of police officers to arrest the wrong person. other cases where 4 different Colorado counties could not undergo the aggressors and enabled violence complicit attackers hit to his victim.

Extreme cases of women witnesses of crimes and that the authorities did not provide witness protection until it is too late. At this time for some women is very important to find criminal legal advice of lawyers pursuit. If you have any questions please send an e-mail to ejecutiva_rchm@hotmail.com. THANK YOU! Phone: 720/841/20/96.