The struggle for the soul of U.S. culture is heating up. White supremacy and anti-immigrant sentiment are on the rise, along with attacks on truth and accountability. Meanwhile, social movements are helping us to reckon with how society (de)values Black lives and the stories of cis and trans women facing sexual abuse. Groups across the country, and around the world, are taking seriously the work of shifting culture as an indispensable part of organizing for social justice.

But how do you go about intentionally shifting culture? The answer depends a lot on your understanding of what culture is and how it evolves. Without a clear theory of culture, it’s difficult to create effective strategies for change. And there are almost as many theories of culture as there are people trying to change it.

For example, in the 18th century, European Enlightenment thinkers proposed a theory of cultural change that is now called “unilineal evolution.” This theory proposes that all cultures evolve in a predictable linear pattern — from primitivism to barbarism to civilization. Western European culture, of course, was placed at the height of civilization. Unilineal evolution has been widely discredited. However, for many years it undergirded Europe’s imperialist project, and its assumptions can still be found lurking in modern discourse, as in efforts to promote development in “underdeveloped” countries.

In this post, I share some prominent theories of cultural change that have informed justice-oriented cultural organizing efforts. Each suggests a different approach to cultural organizing, though they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, some of the best efforts combine approaches. We’re all working from some sort of theory of culture, even if it is just implicit. Being more explicit about how we conceptualize cultural change should help us to be more intentional in making it happen.

1. Cultural Change as Evolution

One way to think about cultural change is that it is analogous to biological change. From this perspective, “cultural traits” (norms, ideas, beliefs, habits, skills, etc.) are passed on to younger generations much as biological traits are. Cultural traits can change over time in response to new needs in the environment. New traits can be introduced and spread through a population via innovation or interaction with other cultures. In this way, culture literally evolves over time, in the Darwinian sense. The analogy is not perfect; for example, cultural evolution moves much faster than biological evolution, and cultural traits can be passed on by non-relatives. Still, decades of research have documented the workings of cultural evolution and how it is similar to, and interacts with, biological evolution.

Richard Dawkins famously coined the word “meme” to describe the cultural analogue to the biological “gene.” According to Dawkins, a meme is a single unit of culture –- for example, the knowledge of how to make a certain tool, or the norm of having fewer children, or the concept of a “meme” itself. Like a gene, a meme is a replicator. It spreads from brain to brain, host to host, like a virus. Memes compete with one another for our attention, our billboard space, and our twitter feeds, and successful memes become self-replicating. Memes may proliferate because they help their hosts (us) survive. But memes can also take on a life of their own, spreading for reasons that have nothing to do with biological survival.

This view of cultural change implies that a cultural organizer is something akin to a dog or plant breeder — introducing and replicating certain cultural traits over others. Of course, we have nothing like the kind of control that a breeder does, working instead in what Dawkins calls the “primordial soup” of culture. But we can take part in the struggle for the survival of the fittest memes. For example, we can identify memes, or cultural traits, from the past and reintroduce them into new contexts. We can build bridges across cultures so that we have a larger pool of cultural traits to choose from. Or we can craft new memes — symbols, rituals, concepts, etc. — and support their spread throughout our communities.

This style of cultural organizing has exploded in recent years with the proliferation of internet hash tags and other symbols that carry memes across the world in an instant. We are learning what kind of memes catch on — or are “sticky” — on these new platforms, and how to actively use them to start new conversations and movements. This theory of cultural change, however, does have its limitations. It suggests a relatively fair playing field upon which the “best” memes will win, obscuring more structural barriers and privileges that affect which ideas come out on top in the cultural arena.

2. Cultural Change as Meaning Making

A second way to think about cultural change is as a process of revising how we collectively make sense of the world. This perspective is rooted in sociological theories such as symbolic interactionism and social constructionism. According to these theories, the important thing about humans is that we are meaning makers. We use our past experiences and interactions to invest the world around us with meaning. The meaning that we make of the world, in turn, shapes how we interact with it.

“Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.”

Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures

This bottom-up understanding of culture leaves a lot of room for human agency. Socially constructed meanings are not permanent. In fact, they require ongoing reinforcement and repair. Every time one of us tells a young boy they shouldn’t wear pink, for example, we reinforce a shared understanding of the male/female dichotomy. On the flip side, every time we challenge the shared way of making meaning — dressing our boy in pink, or not telling anyone their gender at all — we put a tiny dent in the cultural consensus. It is through lots of these tiny communicative encounters that we can see a cultural shift start to take hold.

We don’t make meaning of the world by ourselves, though. We do it through interactions with other people. We communicate through language and other symbol systems, and this impacts how we make sense of our experiences. Over time, through repeated interactions, groups of people develop shared meanings — for example, what it means to be a “man” or “woman” in a particular society. A group’s full web of shared meanings and associated practices is called a culture. To say it another way, culture is an emergent phenomenon, based on billions of small everyday interactions.

This understanding of cultural change encourages us to think not only about large-scale cultural campaigns, but also the importance of small everyday interactions. It resonates with the “personal is political” perspective that came out of the US Feminist movement, and the Environmental Movement’s call to “think globally, act locally.” Our goals may be large in scale, but first we need to attend to ourselves and the ways we interact with our families, our friends, and our fellow organizers. However, as with the evolutionary perspective, these theories may lead us to underestimate the power of social and economic hierarchies to stymie cultural change efforts. For a more structural analysis, we turn to our next theory of culture.

3. Cultural Change as Ideological Struggle

A third way of thinking about cultural change is as a power struggle. This perspective comes to us from critical and Marxist traditions, and is rooted in conflict theory, which argues that societies are made up of social groups competing for resources and power. In this framework, the dominant culture in any society reflects the values, ideologies, and worldviews of the dominant social group. Through its control of institutions like education and mass media, the dominant group is able to project its particular values and ideologies across society in a way that makes them seem normal, neutral, or simply “common sense.”

This is why we can talk, for example, about the culture in U.S. schools or institutions being “white” even if not all of the people in charge are. The underlying assumptions, values, and rules that govern these institutions are aligned with the culture of the dominant (white) group in the country. To the extent that the people in those institutions are a part of that culture and buy into its values, they will find it easier to navigate the institution and earn its rewards. Those who differ too much — who don’t have the right kind of cultural capital — will be marginalized and labeled as deviant.

The dominant group uses its cultural influence to maintain control. By making the status-quo seem fair and just — or at least inevitable — the dominant group earns the allegiance of the majority of the people. After all, if this is the natural order of things, what reason is there to revolt? Gramsci termed this form of domination cultural hegemony. Importantly, cultural hegemony is never complete. There is diversity among elites, and there is always some level of dissent from the population. But cultural hegemony sets the parameters for what forms of dissent are deemed legitimate, and even what kinds of alternatives are imaginable.

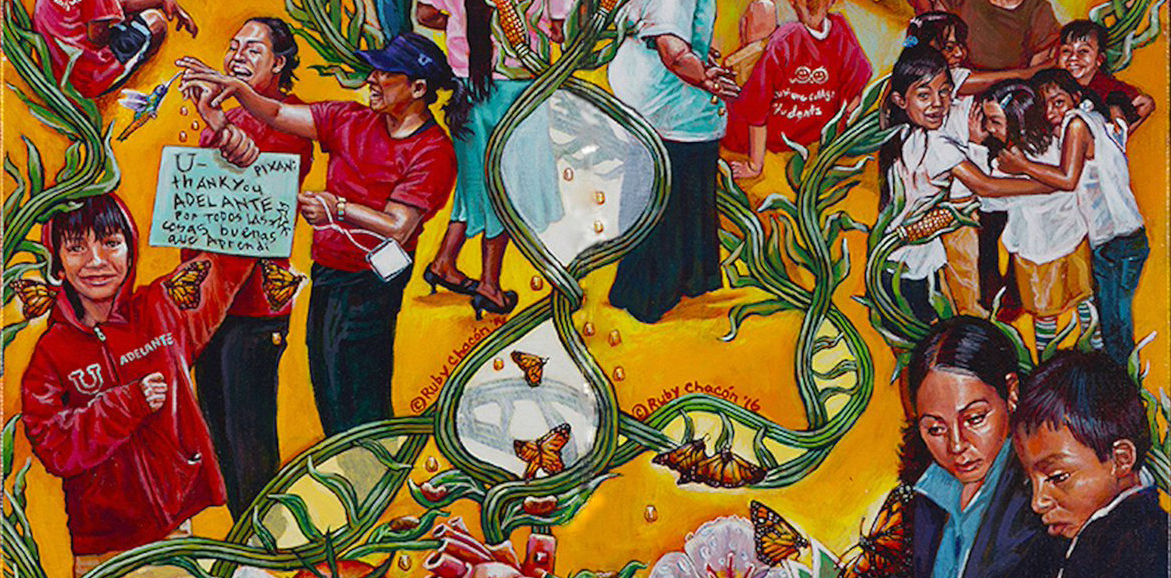

In this framework, the job of the cultural organizer is to find and promote counter-hegemonies. Sub-cultures, often thriving at the margins of mainstream society, develop values and worldviews that challenge the status quo. These counter-hegemonic cultures are all around us, at least in partial form — in hip-hop culture, in Black Twitter, in Indigenous communities, in anarchist collectives, etc. By supporting, promoting, and taking part in the evolution of these sub-cultures, we help amass the cultural resources we need to challenge the powers that be.

According to these theories, cultural resources by themselves are not enough. Cultural struggle needs to be linked to the struggle for economic and political resources as well. Cultural organizers are called on to launch grassroots media outlets that carry countercultural messages; to build new institutions founded on counter-hegemonic values and norms; and to organize with oppressed communities to build power and take control of the economic, social, and political systems.

4. Cultural Change as Counterstorytelling

A fourth way to think about cultural change is as a process of storytelling. This perspective is rooted in the interdisciplinary field of narrative theory. Humans are, as Jonathan Gottschall puts it, “the storytelling animal.” Story is one of the main ways that we make sense of the world and pass along the values, norms, assumptions, and worldviews that make up culture.

For narrative scholars, a “story” is a particular kind of discourse that makes sense of our messy world by “emplotting” it. Story structures differ across cultures, but in western societies they generally include sequences of events with causal links between them (one thing leads to the next), central conflicts that drive the plot forward, and characters who have agency to make choices. Importantly, stories do not exist on their own; they are told. They are social acts. A story involves both a teller and an audience, and it is together that they produce the story’s meaning.

Storytelling serves many purposes. We tell folktales and fables in order to teach children how to behave: don’t shirk your responsibilities, don’t go into the woods at night. We tell friends the stories of our day in order to elicit emotional support and influence how they perceive us. We pass on myths to explain why the world is the way it is and how we should care for it. We narrate our histories in order to solidify a collective or national identity. Even our individual personalities can be understood as stories we tell ourselves in order to find coherence in the complexity of our lives.

Over time, societies develop shared narrative repertoires. These are the stories that “everyone knows” and that communicate what that society deems meaningful, moral, and valuable. This includes specific stories such as folk tales, religious narratives, legends, and popular versions of history. It also includes what the Storytelling Project’s Lee Ann Bell calls “stock stories” or what are often referred to as “dominant narratives.” These are not so much specific stories as genres. These genres show up repeatedly in novels, films, TV shows, and history books. They also serve as blueprints for telling our own personal stories.

For example, take the stock story of the “American Dream.” American Dream stories tell of individuals migrating to the U.S., working hard, and finding a better life for themselves and their children. Barack Obama used this genre at his famous DNC convention speech. The DREAMers movement leveraged this narrative to advance immigration reform. The danger of using dominant narratives is that they tend to reinforce the status quo — in this case upholding ideas about meritocracy and U.S. exceptionalism. Plus, it can be hard to tell alternative stories. Immigrants whose stories don’t match the single story of the American Dream — for example, those who have experienced racism or intergenerational poverty — are silenced, marginalized, and treated as abnormal. If your story doesn’t fit the dominant narrative, there must be something wrong with you.

As this example suggests, stories are deeply connected to questions of power. Which stories can be told, who is able to tell them, and who listens are all arenas of struggle. The Center for Story-Based Strategy refers to this as the “battle of the story.” We see this battle everyday in the media, among policymakers, and in organizing campaigns: groups attempting to advance their version of a story and the way it frames a particular issue or concern. Embedded in these competing stories are different assumptions about what exactly the problem is, how it came about, and how it should be solved.

Stories can shatter complacency and challenge the status quo…They can open new windows into reality, showing us that there are possibilities for life other than the ones we live…They can show us the way out of the trap of unjustified exclusion. They can help us understand when it is time to reallocate power.

Richard Delgado, Storytelling for Oppositionists and Others

Through this lens, the job of the cultural organizer is to be a counterstoryteller. Counterstories, or counter-narratives challenge, subvert, complicate, or counteract the dominant stories that uphold unequal power relationships. A counterstory might be a personal narrative that doesn’t fit into the dominant mold and thus undermines its claim to truth. Or it might be a historical account that has been left out of our history books and that presents a different perspective on the past. Or it might be a visionary narrative laying out more just possibilities for the future. Counterstories are all around us, despite concerted efforts to silence them.

There are many different ways that cultural organizers can support counterstorytelling. For example, the Storytelling Project advocates for a more micro approach, cultivating “counterstorytelling communities” in which multiracial groups can share, critique, and reimagine stories about race. The Center for Story-Based Strategy takes a more macro approach, working with organizing and advocacy groups to develop “narrative strategies” that complement more traditional campaigns. These and other approaches shift culture by uncovering stories that have been silenced, validating the stories of people whose experiences have been marginalized, and inserting new narratives into public discourse.

Conclusion

In the previous sections, I outlined four perspectives on cultural change and what they imply about how organizers can intentionally shift culture. This is far from a complete list. (For example, we’ve barely touched the surface of the complex world of discourse analysis, or the impact of the environment on culture.) However, these are some of the theories that I have found to be most useful in conceptualizing cultural organizing, and have seen expressed by others doing this kind of work. I hope this essay can help further the conversation about our shared understanding of cultural change, and how to enhance our collective struggles for justice.