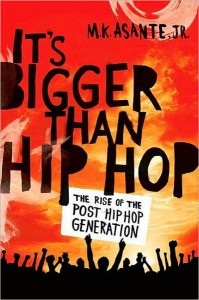

The rap group Dead Prez first informed us that

“It’s bigger than hip hop” in 2000, on their debut album, Let’s Get Free. But it

wasn’t until 2008 that filmmaker, writer,

and professor M. K. Asante Jr. clued us in to just how big it could be. With his

third book, It’s Bigger than

Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post Hop Hop Generation, Asante offers a

compelling vision of a comprehensive youth-led movement for liberation.

The rap group Dead Prez first informed us that

“It’s bigger than hip hop” in 2000, on their debut album, Let’s Get Free. But it

wasn’t until 2008 that filmmaker, writer,

and professor M. K. Asante Jr. clued us in to just how big it could be. With his

third book, It’s Bigger than

Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post Hop Hop Generation, Asante offers a

compelling vision of a comprehensive youth-led movement for liberation.

If you are looking for another book on the history and culture of hip hop, take the title at its word — this is about much more than hip hop. In fact, it explicitly seeks to move beyond many of the constraints, assumptions, oppressions, and other pieces of baggage hip hop carries. That said, Asante obviously loves hip hop — at least the parts of it that are conscious, rebellious, and non-corporate, or that cleave to the original spirit of the culture. Quotes from rap artists like the Coup, Talib Kweli, and Immortal Technique are threaded throughout the book. Asante offers a hip hop timeline, though one that doesn’t just chart the comings and goings of popular music groups. Rather, it starts in 1965, includes all the elements of hip hop, connects hip hop to past social movements, and embeds hip hop in its sociopolitical context. Asante’s critique is targeted at how the hip hop community has been overshadowed and manipulated by the hip hop industry.

It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop offers us a complete social change platform for today’s urban youth activists. The topics are not surprising — prison reform, education, police harassment. After all, you don’t need to explore uncharted territory in order to find systemic injustices. But it is the breadth of Asante’s call to action that makes it stand out, as he deftly weaves together these various oppressions, from corporate ownership of Hip Hop to the struggle for immigrant rights. Much of his analysis comes from an Afrocentric perspective and highlights racism as a central to all the issues raised; at the same time he draws out the intersections with sexism, heteronormativity, xenophobia, and capitalist oppression. For Asante, all efforts towards liberation are intertwined.

While scholarly — in that it is well-researched — It’s Bigger than Hip Hop looks nothing like the books being pumped out by your average college professor. Compelling and passionate, Asante jumps back and forth from birds-eye-view cultural critiques to personal stories, and writes in a range of styles. The most intriguing sections are two invented interviews, one with “The Ghetto” and one with “Hip Hop,” in which Asante plays the student to these conceptual gurus.

One thread that winds through much of the book explores the ways that systemic oppression becomes internalized, particularly among Black youth. The chapter on education focuses almost exclusively on this aspect of educational oppression, outlining how schools inculcate Black youth with messages of Black inferiority. In response, Asante calls on education (particularly self-education) as a way to learn Afrocentric history and promote racial pride. In this way, Asante is following in the footsteps of his father, Molefi Kete Asante, professor and author who first articulated the concept Afrocentricity.

Asante’s contribution to the world of cultural organizing is the idea of the artivist. This label, a combination of activist and artist, is given to people like Paul Robeson, KRS-One, Billie Holiday, and Emory Douglas — and would certainly apply to Asante himself. The artivist is, as the examples above imply, centrally an artist, but one that understands that all art is political — that in fact there is no “arts for arts sake.” Primarily through her art (perhaps along with more traditional activism) the artivist joins the work of liberation as the new face of the African djeli (griot).

Asante’s vision of the artivist is a highly romantic one, reminiscent of the common discourse of the artist as one who simply must make art. But unlike in the traditional notion of the artist, the artivist’s need comes not only from the urge towards creativity but also from the omnipresence of oppression. He envisions the artivist spending “her days and nights feverishly creating in the face of ferocious destruction” (p. 203). Asante states that the Black artist in particular “has to try very hard (by clenching one’s eyes tight and for as long as possible) not to be an artivist” (p. 205).

The spirit that Asante conjures is alive among many of the youth organizers and activists that I have had the honor of meeting. While many of the liberation struggles outlined in this book are taking place disparately, recent years have seen moves to begin uniting young people of color across the country to work towards common goals, such as the Alliance for Educational Justice. As this nascent youth movement grows — inevitably with a soundtrack heavy on hip hop — they could do worse than follow Asante’s liberatory platform.

if these kids payed taxes maybe I’ld lissen to them.otherwise….SHUT THE HELL UP,TAKE YOUR DRUGS AND GO TO SLEEPY BYE……………AND WHATEVER YOU DO////DONT COME TO SOUTH CAROLINA UNLESS YOU EXPECT TO STAY IN OUR LAND!!!!!!