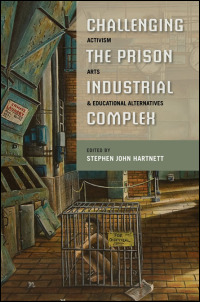

Challenging the

Prison-Industrial Complex: Activism, Arts, & Educational

Alternatives

Challenging the

Prison-Industrial Complex: Activism, Arts, & Educational

Alternatives

Edited by Stephen John Hartnett

University of Illinois Press, $25.00

I’ve been working on an edited volume about the school-to-prison pipeline, and taking the opportunity to check out recent books on the topic. One of the more rich and intriguing tomes I have come across is Challenging the Prison-Industrial Complex: Activism, Arts, & Educational Alternatives. The book brings together scholars and educators — along with incarcerated poets and visual artists — to illuminate the workings of the prison-industrial complex and share strategies for confronting it.

The book is split in two parts. The first — Diagnosing the Crisis — is dedicated to understanding the prison-industrial complex (PIC), the web of government and for-profit institutions that monitor, control, discipline, and incarcerate millions of US residents. This country, Hartnet argues, has become a “punishing democracy,” a system in which “punishment has become a driving force in contemporary American life” (p. 6).

The chapters span an impressively wide range, illuminating multiple facets of the PIC. Erica Meiners uncovers the economic underpinnings of the PIC, and the ways that surveillance and control are privatizing public space. Julilly Kohler-Hausmann offers a compelling and disturbing account of how our domestic police force has been increasingly drawing on military tools, strategies, and metaphors since the Vietnam war. Rose Braz and Myesha Williams outline the school-to-prison pipeline, and the increased policing of schools, while other pieces look at stereotypes in media, and the “war on drugs.”

The second half of the book — Practical Solutions, Visionary Alternatives — offers a series of stories about on-the-ground work being done to engage with, shift, and challenge the PIC. I would hesitate to call them “solutions,” given the daunting task they take on, but they certainly offer practical actions that real people are taking, and begin to paint a picture of a different world — one in which we see the humanity of everyone, and truly question the ways that we engage with one another and the conflicts that arise between people.

Of particular interest to readers of this blog, the arts play a very large role in this section of the book. It begins with Buzz Alexander, writing about the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) at the University of Michigan. This program — which I was a part of in college — runs theater and writing workshops in prisons, juvenile detention centers, and public schools, as well as an annual visual art show. Alexander gives a bold yet humble account, offering a taste of the messiness and the promise of this work, to which he has given so many years. Robin Sohnen shares the work of the Each One Reach One program, which does playwriting and tutoring in prisons, and Jonathan Shailor recounts his experiences doing Shakespeare in prisons. While each of these programs has a different focus, pedagogy, and theory of change, together they demonstrate the potential of artistic programming to build humanizing relationships between those inside and outside of the prison system; to help individuals develop and grow; to spread awareness of the oppressions of the system and of the humanity of the incarcerated; and to begin much-needed dialogue about the future of our democracy.

Throughout the book, readers are treated to pieces of poetry from incarcerated men and women, and a stunning set of images from the PCAP Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners. These pieces bring some concreteness to the stories told by the authors above, and connect a reader with not just the idea of prisoners but incarcerated humans in the particular.

The book as a whole, and the scholar-educator-artist-activists within, seek to shift our country from a punishing democracy to an abolition democracy. They are calling for the abolition of the prison-industrial complex. Drawing on writing by Angela Davis, Hartnett argues that prison abolition is not a negative effort of simply shutting down prisons, but a proactive process of creation — which is perhaps why artistic practice can play such an important role. He says that “shutting down the prison-industrial complex will require nothing less than a revolution — the question is not only how to abolish prisons, but how to reimagine a democracy that does not need such institutions” (p. 4).