Photo: Mirror Shileds at Standing Rock, Designed by Cannupa Hanska Luger

These days, it seems like we are in a constant state of emergency. Last week’s terror attack against anti-racist protesters in Charlottesville is only one in a string of local, national, and international crises. Whether its a police shooting, an illegal pipeline project, a ban on Muslims entering the US, or the threat of nuclear war, we are bouncing from one disaster to the next with head-spinning rapidity. And this is to say nothing of long-simmering, chronic emergencies like poverty, climate change, and colonialism. In this context, we can be forgiven if we’re a bit unsure about where to start.

A new report out from the US Department of Arts and Culture (USDAC) offers an intriguing path forward. In Art Became the Oxygen: An Artistic Response Guide, the USDAC argues that “crises need creativity.” Art and cultural work, they propose, are essential for responding to disasters — whether they be natural, technological, human-made, or all of the above. The USDAC first shared this idea last winter in it’s policy and action platform, Standing for Cultural Democracy. Now, over the course of 74 pages, the USDAC lays out the why and how. It is well worth a read from start to finish.

What is Artistic Response?

As Hurricane Sandy made its way toward the east coast in October of 2012, an array of local, state, and national emergency management systems went into effect. Even before landfall, the Federal Emergency Management System (FEMA) and its New York counterpart began setting up distribution points for meals, blankets, and water. In the hours after the storm hit, federal agencies and nonprofit organizations mobilized thousands of people and hundreds of millions of dollars to feed and clothe survivors, get the power back online, and clean up the physical impact of the disaster. FEMA and its partners were publicly lauded for their efforts.

Less well recognized, and far less well funded, was the work of volunteers like those at the Park Slope Armory in Brooklyn. The Armory had been turned into an evacuation shelter for 300 elderly and special needs evacuees. Seeing that these individuals had needs beyond shelter, food, and water, a local city councilman asked Caron Atlas of Arts & Democracy to organize cultural and wellness activities onsite. Soon, the Armory was filled with volunteer- and evacuee-led activities: music, dance, films, knitting, massage, religious services, therapy dogs, and more. Artists came from all around to run workshops and share their talents. Atlas reflects on the value of this experience:

“I’ve always known that arts and culture had the power to heal, but this direct experience proved to me how extraordinary they could be in a disaster. Above all, our work helped return peoples’ dignity and respect. They went from being an evacuee in a row of cots to being the incredible human beings that they truly are — a woman who got her PhD years before it was common for women to do so, a Jazz drummer, a torah scholar, a painter, amazing knitters.”

This is just one example of what Amelia Brown calls “emergency arts,” a combination of artistic practice, emergency management, and community development. Drawing on her own experience in New Orleans during and after Hurricane Katrina, Amelia Brown works to build collaborations among artists, community members, and emergency management agencies to support resiliency, healing, and recovery in the midst of disaster. Even as she addresses the deep trauma and tragedy of disaster, Brown recognizes opportunities as well.

“Serving in New Orleans helped me develop a deeper understanding that emergencies can lead to opportunities. One of the most precious opportunities is to rebuild community with people gathered around an emergency who were once strangers and become family. These relationships are one of our greatest community assets.”

What does Artistic Response Look Like?

As Brown lays out in the Guide, emergencies come in many forms. They can be “acute shocks” like an instance of violence or a flood. They can also can be “chronic stresses” like unemployment or water deficiencies. Emergencies can be natural, technological, or human created. In fact, every crisis, she explains, is actually multiple crises. Natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina can be exacerbated by human error and discrimination. Acute shocks can uncover deep, festering divisions in our society. For example, the murder of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville was not only a startling act of violence. It was also symptom of our country’s inability to come to terms with its long history of white supremacy.

Different emergencies require different responses. In Art Became the Oxygen, artistic responses are sorted into three broad categories:

1. Care, Comfort, and Connection

Traditional emergency management systems are focused first and foremost on personal safety, ensuring that people survive an acute disaster intact. Artistic response can help with the next steps: creating spaces of safety, reasserting strength and dignity, and connecting with one’s community in preparation for the long, collaborative process of recovery. This is what took place at the Park Slope Armory after Hurricane Sandy. The tools of community-based arts — like the facilitation collaborative art making rooted in people’s experiences and cultures — are well suited to this work.

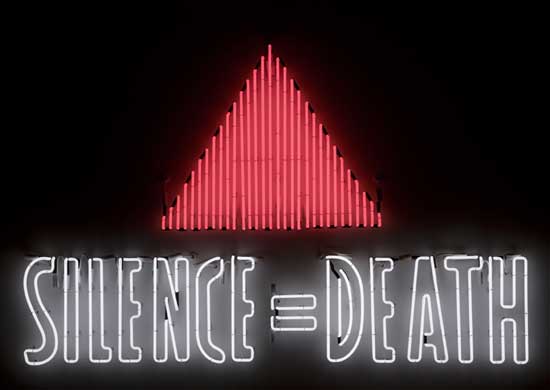

2. Protest

Not all emergencies receive the kind of outpouring of support that we saw with Hurricane Sandy. Often political pressure is needed to demand an effective response. In this context, the arts can be used to highlight emergency situations, uncover root causes, generate empathy for those impacted, and share counterstories to those in mainstream media. In addition, disasters often clarify the need for more systemic political and social change — whether that’s more investment in infrastructure or police reform. Artists can draw on a long history of protest art to support movements for systemic change.

3. Reframing and Resilience

Once initial disaster relief efforts wind down, the hard work of recovery begins. Building back up the physical, emotional, spiritual, or social fabric of community is slow, patient work, and requires high levels of collaboration. Community artists can support this process in numerous ways, such as making space for storytelling, creating opportunities to heal from trauma, bringing community members together to strengthen social ties, and helping to imagine a strong, resilient future.

Artists and cultural workers of all stripes are called to action in times of emergency: muralists, graphic designers, digital media artists, photographers, dancers, musicians, theater artists, storytellers, artisans, etc. Most of the work featured in the Guide is of a community-engaged, collaborative nature. However, artists who work on their own can also play valuable roles, particularly in the category of protest. The Guide is full of examples to inspire and inform new efforts. For examples, check out the work of Transforma in New Orleans, Dancing for Justice, Project Jukebox, and We Are The Storm, to name just a few.

What Does Effective Artistic Response Take?

Artistic response is necessarily diverse and flexible, taking into account the particularities of each emergency, so there is no one list of best practices. However, the Guide offers a lot of valuable advice for those considering getting involved. Any community engaged artistic project requires careful attention to local history, culture, and policy, and demands well developed skills in group facilitation, collaboration, and self understanding. Working with people living through trauma and stress heightens the importance of these skills. This is not an area of work to enter lightly.

Working in collaboration with other organizations or agencies brings in a whole other raft of concerns. In fact, almost a quarter of the Guide is dedicated to building bridges between artists and emergency management agencies. This is an area of exciting possibility, as well as huge barriers. Artists and agencies work from different paradigms, use different language, and measure their success in different ways. While goals may overlap, priorities may not be aligned. The USDAC suggests that artists interested in such partnerships study the basics of emergency management, approach agencies with respect, build trust and foster honest conversation about risks, and work as intermediaries that can translate between communities and agencies, among other advice.

Artistic responders, the USDAC stresses, are not saviors. They are supporters, partners, learners, and catalysts. They recognize that while emergencies inevitably affect some more than others, we all have a shared stake in building our collective strength and resilience. Amelia Brown offers this vision of a future where artistic response is the norm:

“Effective development of this field includes building relationships, policies, procedures and structures that support artists at every level of emergency management. Collaborations in this field will change the future of emergency management. I envision a time where there will be no emergency management plans that do not have dedicated arts policies and procedures. There will be no emergency management agencies that do not have artists as part of their leadership team. There will be no community organizations that do not recognize and support the value of artists in addressing emergencies in their communities. There will be Emergency Arts.”

Want to learn more? Read the report, and then join the conversation on August 28th for the Art Became the Oxygen online “salon,” featuring Carole Bebelle of Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans; Michael O’Bryan, of the Village of Arts and Humanities in North Central Philadelphia; and Amber Hansen, South Dakota-based visual artist and Co-director of Called to Walls.