Essay by Paul J. Kuttner, 2015

“Cultural organizing exists at the intersection of art and activism. It is a fluid and dynamic practice that is understood and expressed in a variety of ways, reflecting the unique cultural, artistic, organizational, and community context of its practitioners. Cultural organizing is about integrating arts and culture into organizing strategies. It is also about organizing from a particular tradition, cultural identity, community of place, or worldview.”

— from Cultural Organizing: Experiences at the Intersection of Art and Activism1

The term cultural organizing appears occasionally in writing about activism and social movements in the twentieth century. It has been used, for example, in reference to the cultural strategies of Popular Front organizers during the 1920s and 1930s,2 and to the work of Zilphia Horton and others at the Highlander Center in Appalachia.3 In his book, The Culture War in the Civil Rights Movement, historian Joe Street uses the term to describe the important roles that artists played in the civil rights and Black liberation struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Street defines the term broadly as indicating “when activists made an explicit attempt to use cultural forms or expressions as an integral, perhaps even dominant, part of the political struggle and when, during this process, attention was drawn to the intrinsic political meaning of the cultural activity.”4

In recent years, cultural organizing has emerged as a multidisciplinary community of practice at the intersection of art, cultural work, and social change. A growing number of individuals and organizations have begun using the term to describe their work. Cultural organizing has been a topic at a number of national conferences, public conference calls, workshops, and trainings around the country, run by organizations such as Netroots Nation, the National Conference for Media Reform, and the Arts and Democracy Project. For over three years, The Highlander Research and Education Center has run the Zilphia Horton Cultural Organizing Fellowship, which trains artists as cultural organizers.

Growing interest in cultural organizing has led to an increase in efforts to define it and theorize about it. For example, Cohen-Cruz describes cultural organizing as “various forms of artistic communication that provide a cultural dimension to community organizing in order to expand and humanize a social movement.”5 Meanwhile, the Highlander Center defines it as “the strategic use of art and culture to promote progressive policies with marginalized communities.”6 The definition that I have found most useful comes from the Arts and Democracy Project, which, in 2011, brought together a group of artists, organizers, and cultural organizers to explore ways of integrating creativity and imagination into organizing and community building practice. At this gathering, the group developed the following working definition of cultural organizing:

Cultural organizing exists at the intersection of art and activism. It is a fluid and dynamic practice that is understood and expressed in a variety of ways, reflecting the unique cultural, artistic, organizational, and community context of its practitioners. Cultural organizing is about integrating arts and culture into organizing strategies. It is also about organizing from a particular tradition, cultural identity, community of place, or worldview.7

As this definition suggests, cultural organizing is a highly varied field, encompassing practices as diverse as media activism, story circles, public theater, cultural festivals, and documentary films. However, there are some key features that hold across most, if not all, efforts using the term. Firstly, cultural organizing efforts have cultural goals, meaning that they seek to affect people’s ideologies, identities, and/or ways of being together. Secondly, cultural organizing efforts utilize the language of culture — art, ritual, story, celebration — in order to carry out their work. Thirdly, cultural organizing is strategic, in that it works towards long-term, collective aims as opposed to being focused solely on creating opportunities for individuals to express themselves and learn (although that is often a part of it as well). Fourthly, cultural organizing is about bridging the worlds of art and organizing by making explicit links, 1) between cultural goals and more concrete policy goals; 2) between artists and professional organizers; and/or 3) between artistic practices and organizing techniques.

Within this umbrella, three general approaches to cultural organizing have emerged. Each builds on different historic precedents, overlaps with different fields, and offers somewhat different conceptualizations of “culture” and “organizing.” I refer to these approaches as the cultural strategy approach, the community arts approach, and the cultural integration approach.

The Cultural Strategy Approach

The cultural strategy approach focuses heavily on the use of artistic products as a way to shift public discourse around social issues. These efforts tend to involve explicit partnerships between practicing artists and professional organizers, or the organizing of artists around a specific issue or movement. The goal of these efforts is to develop a “cultural strategy” alongside a more traditional political strategy, in order to “shift public sentiment and forge a new collective consensus around a social problem or issue.”8 The underlying theory is that ideas and action are connected, so in order to change people’s actions (including the policies they make) organizers must first change the ways people think about and understanding the world. Artistic products are used to spark public dialogue, insert alternative ideas into public discourse, and catalyze collective action.

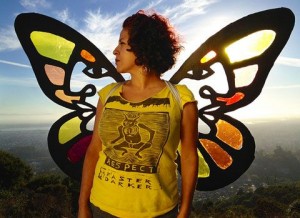

Bay-Area cultural organizer Favianna Rodriguez promotes a cultural strategy approach to cultural organizing. Rodriguez is a printmaker and activist in the immigrant rights movement. She is best known for her series of prints featuring a butterfly and the phrase “migration is beautiful.” Rodriguez designed this image as a way to counter negative stereotypes about immigrants, and to reframe the public’s conception of immigration. As Rodriguez puts it, “The butterfly is the symbol to talk about the beauty of migrants as they are moving from place to place. Just like butterflies migrate in order to survive, people migrate in order to survive.”9 Her images have been adopted by many immigrant rights groups for use in actions and campaigns. Moreover, through her organization CultureStrike, Rodriguez connects and organizes other artists to create visual, written, and video art in support of the immigrant rights movement.

This approach to cultural organizing follows in the footsteps of artists like Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party; the poster campaigns of the AIDS movement group ACT UP; and the organizing of socially-minded artists in the 1930s.10 When proponents of this approach talk about “culture,” they are often referring to the dominant culture, and their efforts to challenge, shift, or supplant it. This approach is “organizing” in the sense that it involves organizing artists around a cause, or partnerships between artists and other change agents in support of a larger, organized campaign or movement. This approach has much in common with recent efforts to enhance the use of narrative, media, and spectacle in organizing campaigns.11 The Culture Group, a collaboration of social change experts and cultural workers led by Jeff Chang, is a proponent of this kind of approach.

The Community Arts Approach

The community arts approach to cultural organizing, in contrast, is designed around the process of creating works of art and other cultural products. Such efforts may include professional artists as teachers or facilitators, but are heavily geared towards engaging community members who may not see themselves as artists. The process is designed to draw on local cultural resources: the stories, voices, perspectives, practices, and/or art forms of the community involved in the organizing. While final products may be used to engage outsiders and spark dialogue, equally important is the artistic process itself and the experience of those involved.

The theory underlying this approach is that the artistic process itself can serve as a form of organizing. Community members build relationships, research the issues in their community, and develop collaborative artistic actions. Through this process, a community develops new leaders, comes to agreement around collective goals, and increases its capacity to create change. Moreover, because the process is rooted in the particular cultural practices and stories of the community, this approach to cultural organizing can help to promote cultural pride, community cohesiveness, collective efficacy, and the development of empowering cultural identities. These efforts are often linked to traditional organizing campaigns, but may also be focused squarely on build the long-term capacity of the community to act effectively.

One example of this kind of approach is the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program, run by the American Friends Service Committee’s Pan Valley Institute (PVI), a popular education center in California’s Central Valley. Rather than bringing in outside artists or organizers, the Tamejavi program supports fellows from different local immigrant communities in becoming “cultural keepers, oral-tradition masters, leaders, and organizers” for their communities. Fellows are trained in popular education, participatory action research, and cultural organizing, which PVI defines as “a community-building process in which people share cultural traditions and artistic expression with one another to build stronger, more active communities.”12 Fellows are charged with creating a local working group and conducting a community assessment and cultural inventory, with the goal of understanding the community’s central concerns and cultural resources. They then collaborate on cultural projects that address these concerns, “organizing creative spaces, cultural practices, and heritage education programs…within and across their own communities.”13

This approach to cultural organizing falls most squarely into the realm of community-based arts. The “culture” with which it engages is, first and foremost, the culture of those involved in the organizing. It begins with existing cultural resources, and works to develop stronger community ties, cultural pride, cross-cultural understanding, etc. It is “organizing” because it builds relationships and social capital, uncovers key community issues, supports the development of community leaders, and can support or lead to other forms of action.

The Cultural Integration Approach

The cultural integration approach to cultural organizing is about integrating local cultural practices, forms of expression, and worldviews into a community organizing model. It is based on the idea that for community organizing to be effective and sustainable, it must be rooted in local culture and make room for people to “bring their full self” to the table.14 Organizing, particularly when it is heavily focused on strategy and winning campaigns, can carry a heavy toll on community members. Making room for cultural expression and celebration can be a source of healing and rejuvenation. Moreover, existing organizing models may not resonate across cultures. Cultural organizers argue that local culture should drive the shape and practice of organizing.

One example of the cultural integration approach is the Main Street Project’s Raices program, which works with rural Latina/o communities in Iowa, Minnesota, Idaho, and Oregon. Founder Amalia Anderson was previously involved in election-related organizing, and found that “traditional political organizing did not resonate with rural Latinos.” In response, she created Raices, looking to engage in organizing that “respects a slow pace of work, isn’t tied to election cycles, and focuses on base building and relationship building.”15 Raices works with communities to address common issues through a process of community interviews and story collection, followed by community gatherings, or “encuentros.” Throughout, Raices works to develop a sense of shared community and cultural identity through food, music, language, and dance. As Benavente & Richardson write, “This approach to cultural organizing is less about acquiring or utilizing a specific set of skills and more about organizing from who you are, where you come from, and how your life experience and ways of knowing impact the way you move in the world.”16

Like the community arts approach, the cultural integration approach is focused on the culture of those doing the organizing. It is organizing because it is part and parcel of recognizable community organizing effort. Many community organizing groups integrate cultural practices and perspectives into their work without using the term “cultural organizing.” Cultural rootedness is often a key aspect of long-term, successful community organizing.17 Tufara Waller Muhammad, from the Highlander Center, argues that this kind of cultural work has always been a part of the Southern school of organizing.

“Every organizer should be using art and culture as a strategy to help people build bridges…I come from a long organizing tradition that includes the Ella Baker Schools, and people like Hollis Watkins and Bernice Johnson Reagon, among others, where art and culture have always been a part of organizing. When I started working outside the South, the thing that freaked me out was organizing with no cultural or artistic component.”18

By adopting the term “cultural organizing,” organizers like Anderson are making an explicit attempt to forefront cultural responsiveness and rootedness in an increasingly professionalized field.

Conclusion

By outlining these three different approaches, I hope to give a sense of the spectrum of efforts that have adopted the term “cultural organizing” for their own. The lines between the approaches, however, are very blurry, and the approaches can be combined in intriguing ways. For example, the Thousand Kites initiative at Appalshop includes a professional documentary film about prisons, as well as a play that can be adapted and performed by local communities.19

Cultural organizing is not inherently progressive. As Caron Atlas of Arts and Democracy explains, “[Cultural organizing] can be done to unite people through the humanity of culture and the democracy of participation. It can also be used to divide people though fear and polarization. Karl Rove, in his appeal to the Christian Right, is a master of cultural organizing. So are thousands of progressive grassroots leaders working for social and economic justice. What is different are the values, principles, and vision for the future (and definition of whose future) that lie at the heart of the organizing.” 20However, when the group that Arts & Democracy gathered in 2011 designed their working definition, they also developed a set of principles that take a strong, progressive philosophical stand. According to this group, cultural organizing:

- Values multiple ways of knowing and being

- Reconceptualizes power and power relationships

- Prioritizes the centering of a creative process to address change

- Addresses the issues people face in their communities

- Moves people toward a place of action

- Develops new leadership

- Is based on the lived experiences of those participating

- Deepens analysis, i.e., gain knowledge, engage with theories of social change & liberation

- Allows participants to bring their full self

- Confronts oppression and privilege

- Involves whole communities in a transformative process

- Process and outcome are valued equally

- Real emphasis on listening and story-telling as a method for generating knowledge and understanding 21

For the most part, the practices that make up cultural organizing efforts are not new, though they have evolved with changing times and new technologies. Not only do cultural organizers build on past cultural organizing efforts, but they also draw on well-worn practices from the fields of arts activism, community-based arts, and community organizing, among others. However, the fact that increasing numbers of individuals and groups are adopting the term “cultural organizing” suggests that there is a need to delineate a particular arena of community-based practice that draws its inspiration from both the art world and the organizing world. This area of practice is more fully committed to cultural expression and artistic practice than most organizers, and more connected to traditional organizing than most political artists. As Atlas puts it, “The question is not whether this is art or whether it is activism. It is a combination of the two — a hybrid that needs to be understood on its own terms.”22

Notes

Photo at top: A Taiko Drumming Performance by the Genki Spark http://www.thegenkispark.org/

- Benavente, J., & Richardson, R. L. (2011). Cultural organizing: Experiences at the intersection of art and activism. Washington, D.C.: Animating Democracy. Retrieved from http://animatingdemocracy.org/resource/cultural-organizaing-experiences-intersection-art-and-activism

- Denning, M. (1998). The cultural front: The laboring of American culture in the twentieth century. London: Verso.

- Highlander Research and Education Center. (2013). Strength through song at the Zilphia Horton Cultural Organizing Institute. Retrieved from http://highlandercenter.org/strength-through-song-at-the-zilphia-horton-cultural-organizing-institute/

- Street, J. (2007). The culture war in the civil rights movement. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 8

- Cohen-Cruz, J. (2010). Engaging performance: Theatre as call and response. New York: Routledge. p. 90

- Highlander Research and Education Center. (2014). Zilphia Horton Cultural Organizing Project goes to Dallas! Retrieved from http://highlandercenter.org/zilphia-horton-cultural-organizing-project-goes-dallas/

- DeNobriga, K. (2011). Cultural organizing for community recovery, New Orleans. Retrieved from http://artsanddemocracy.org/detail-page/?program=organizing&capID=11

- The Culture Group. (2014). Making waves: A guide to cultural strategy. Author. Retrieved from http://theculturegroup.org/2013/08/31/making-waves/

- Kuttner, P. (2013b). Interview with cultural organizer Favianna Rodriguez. Retrieved from /?p=993

- Lampert, N. (2013). A people’s art history of the United States. New York: The New Press.

- Boyd, A., & Mitchell, D. O. (2012). Beautiful trouble: A toolbox for revolution. New York: OR Books. Reinsborough, P., & Canning, D. (2010). RE:imagining change: How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

- Kohl-Arenas, E., Nateras, M. M., & Taylor, J. (2014). Cultural organizing as critical praxis: Tamejavi builds immigrant voice, belonging, and power. Journal of Poverty, 18(1), 5–24. p. 10 & 12

- Kohl-Arenas, E., Nateras, M. M., & Taylor, J. (2014). Cultural organizing as critical praxis: Tamejavi builds immigrant voice, belonging, and power. Journal of Poverty, 18(1), 5–24. p. 7

- DeNobriga, K. (2011). Cultural organizing for community recovery, New Orleans. Retrieved from http://artsanddemocracy.org/detail-page/?program=organizing&capID=11

- Benavente, J., & Richardson, R. L. (2011). Cultural organizing: Experiences at the intersection of art and activism. Washington, D.C.: Animating Democracy. Retrieved from http://animatingdemocracy.org/resource/cultural-organizaing-experiences-intersection-art-and-activism p. 4

- Benavente, J., & Richardson, R. L. (2011). Cultural organizing: Experiences at the intersection of art and activism. Washington, D.C.: Animating Democracy. Retrieved from http://animatingdemocracy.org/resource/cultural-organizaing-experiences-intersection-art-and-activism p. 4

- Warren, M. R., Mapp, K. L., & the Community Organizing and School Reform Project (2011). A match on dry grass: Community organizing for education reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Benavente, J, & Waller Muhammad, T. (2008). Planning the revolution over collards. Retrieved from http://artsanddemocracy.org/detail-page/?program=bridge&capID=65

- Cohen-Cruz, J. (2010). Engaging performance: Theatre as call and response. New York: Routledge.

- Atlas, C. (Ed.). (2006). Cultural organizing: An exchange among Amalia Anderson, Caron Atlas, Jeff Chang, Dudley Cocke, Samuel Orozco, Peter Pennekamp, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, and Ken Wilson. Grantmakers in the Arts Reader, 17(2). Retrieved from http://www.giarts.org/article/cultural-organizing

- DeNobriga, K. (2011). Cultural organizing for community recovery, New Orleans. Retrieved from http://artsanddemocracy.org/detail-page/?program=organizing&capID=11

- Atlas, C. (Ed.). (2006). Cultural organizing: An exchange among Amalia Anderson, Caron Atlas, Jeff Chang, Dudley Cocke, Samuel Orozco, Peter Pennekamp, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, and Ken Wilson. Grantmakers in the Arts Reader, 17(2). Retrieved from http://www.giarts.org/article/cultural-organizing