Last week’s historic Supreme Court decision on marriage equality has sparked celebrations of love around the country, as well as calls for a refocusing on more intractable issues like LGBTQ discrimination, homelessness, and hate crimes. This is a time to honor the hard work that has been done, while situating this win in the context of a much longer struggle. Here at CO, this seems like a great moment to look back at some of the artists and cultural workers who have supported the movement in the US by challenging mainstream narratives of gender and sexuality, and by offering transformative visions of LGBTQ life and identity. It’s also a good time to check in on some of the newer artists who will carry this work into the future. There’s far too many to name in one post, but I’ll share a few of my favorites — please feel free to add more in the comments!

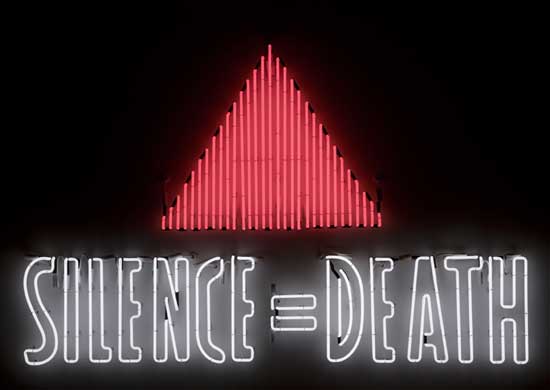

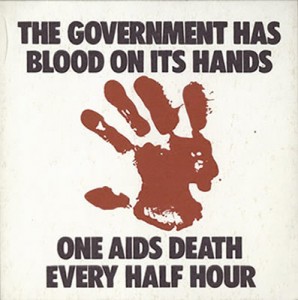

Gran Fury & ACT-UP

I just have to start with Gran Fury, the small artist collective that grew out of the ACT-UP organization during the 1980s and has became a touchstone for cultural organizers ever since. Gran Fury’s guerilla-style visual art campaigns captured the urgency of the struggle against AIDS at a time when so many were dying, and demanded public space for gay voices and images. In the midst of a narrative that focused blame and fear on gay men and ignored other victims of the plague, Gran Fury and ACT-UP rewrote the narrative through bold visuals and brief catch phrases. In Gran Fury’s art, people living with AIDS received the empathy they deserved (“All People with AIDS are Innocent”) and the public figures who ignored the crisis were recast as villains (“Silence=Death”). As activist-artists working in movement organizations as well as the art world, Gran Fury and ACT-UP had a lasting impact on AIDS, the LGBTQ movement, and the arts. As former member Loring McAlpin put it, “I think what we accomplished was to drive a wedge into public discourse and open a space where AIDS could be talked about in all its dimensions.”

The Lesbian Avengers

The 1990s direct action group the Lesbian Avengers shared much of the same spirit (and many members) with ACT-UP. The Lesbian Avengers challenged homphobia in all its forms through creative actions, or what they called “zaps.” In the Lesbian Avengers handbook, they state “Avoid old stale tactics at all costs. Chanting and picketing no longer make an impression. Standing passively still and listening to speakers is boring and disempowering.” They, in turn, could be found running a marching band through a school singing, “Oh When the Dykes come Marching in,” or eating fire in response to the burning murders of two LGBTQ individuals (“The fire will not consume us. We take it and make it our own.”). According to former member Kelly Cogswell, “Every time the Avengers pulled off an action, we weren’t just making lesbians visible or trying to change society. We were changing lesbians. Creating a new kind of dyke who saw public space as hers, who could step out into the street and make noise, be herself, feel at home in the world.”

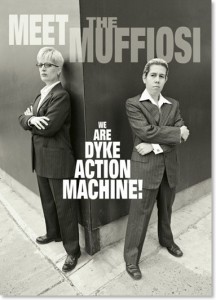

Dyke Action Machine

In 1991, not long before the Lesbian Avengers got started, artist Carrie Moyer and photographer Sue Schaffner launched the Dyke Action Machine (DAM). Inspired by the Situationists, this culture jamming duo began running poster campaigns inserting lesbian images into commercial advertisements (e.g Gap, Kalvin Klein), challenging the lack of queer representation in popular culture. Over time they have used websites, mailers, t-shirts, and other products to critique mainstream media’s increasing attempts to cater to the gay and lesbian “demographic,” while at the same time challenging mainstream gay rights efforts (including the fight for gay marriage). They remain a sort of radical, queer, humerous conscience for the movement.

Alison Bechdel & Howard Cruise

Among the growing number of comics to address LGBTQ issues, two authors stand out. Alison Bechdel — best known now for her award-winning comic memoir Fun Home — became a cultural trailblazer with her strip Dykes to Watch Out For, which ran from 1983 to 2008. The strip is philosophically deep, politically astute, and hilarious. Dwight Garner, in the New York Times, suggested that DTWOF, “has been as important to new generations of lesbians as landmark novels like Rita Mae Brown’s “Rubyfruit Jungle” (1973) and Lisa Alther’s “Kinflicks” (1976) were to an earlier one.” Meanwhile Howard Cruise’s 1995 book Stuck Rubber Baby is simply one of the best graphic novels to date on any topic. It’s story of a young gay southern white man getting involved in civil rights organizing in the 1960s is moving, terrifying, and beautiful. Prior to that, Cruise was an openly-gay underground comics artists (who introduced a gay character in his comic in 1976) and who wrote an ongoing piece for The Advocate.

Looking Forward

What issues are LGBTQ young arts-activists addressing now, and where are they headed? While gay and lesbian individuals still face discrimination and, often, physical danger because of their sexuality, the context of the movement has changed. With the increasing presence of gay and lesbian images in popular culture, it is no longer so radical to write a lesbian character into a comic, or to put up advertisements featuring two men kissing. In response, artists are pushing into more complex and intractable aspects of heteronormativity. They are addressing LGBTQ narratives that don’t fit into clear binaries, that don’t align with mainstream visions of loving relationships, and that were marginalized in earlier movement efforts.

Two trends stand out. The first is definitely an increased focus on transphobia, and on the lives and voices of transgender/gender-diverse people. Just check out this list from the Museum of Transgender Hirstory and Art covering some of the great work done in 2014. A second, and related, trend is giving more attention to intersectionality — the ways that LGBTQ experiences intersect with other axes of oppression. Artist-activists like Julio Salgado and Favianna Rodriguez are exploring the intersection of queerness and immigration. Nia King has been cataloging conversations with queer and trans artists of color on her podcast (which is now a book — review to come soon!). And theater group Sins Invalid adds in a focus on (dis)ability alongside race and gender/sexuality. There are many more I could name, and surely many, many more I don’t yet know about. If these are the cultural leaders who are going to lead us into a new future, there is much reason for hope.