Below is part two of my interview with Nicolas Lampert, author of A People’s Art

History of the United States. Click HERE to read part 1 of the interview, in

which we discussed his early development as an artist and activist, his

work with Justseeds Artists Cooperative, and how

Howard Zinn encouraged him to write his book. In part 2, we discuss A People’s

Art History of the United States, the rich legacy of arts

activism in the US, and the importance of debating the tensions and

contradictions in this work.

What was your vision when you first began writing A People’s Art

History, and how did that vision change over the course of the eight

years you worked on the project?

Prior to starting the

project, I had been writing articles on art and activism for Clamor

magazine, doing interviews with activist artists, and I co-edited a

book called Peace Signs: The Anti-War Movement

Illustrated, so that gave me some experience in writing and

developing my voice. But really, Howard Zinn gave me this unbelievable

opportunity, which was such a gift. He planted the seed of the idea and

introduced me to The New Press and thankfully they were really intrigued by

the proposal. I told them that I was not a PhD historian, I was an activist

artist, and I wanted the book to be useful to artists and activists, and for

it to be accessible to a general audience. The editor at the New Press said,

“That’s perfect, that’s exactly what we’re looking for.” So all the stars

were aligned to do the book.

Prior to starting the

project, I had been writing articles on art and activism for Clamor

magazine, doing interviews with activist artists, and I co-edited a

book called Peace Signs: The Anti-War Movement

Illustrated, so that gave me some experience in writing and

developing my voice. But really, Howard Zinn gave me this unbelievable

opportunity, which was such a gift. He planted the seed of the idea and

introduced me to The New Press and thankfully they were really intrigued by

the proposal. I told them that I was not a PhD historian, I was an activist

artist, and I wanted the book to be useful to artists and activists, and for

it to be accessible to a general audience. The editor at the New Press said,

“That’s perfect, that’s exactly what we’re looking for.” So all the stars

were aligned to do the book.

Structure-wise I knew that I wanted to move through U.S. history chronologically. I also knew pretty early on that I didn’t want to do an exhaustive survey. I wanted to select specific examples and write critically about the intersection of art and activism. For instance, I knew I wanted to write about the Wobblies, and I could have selected multiple examples where the I.W.W. used art in their organizing — Joe Hill’s cartoons, the graphics of Ralph Chaplin, Mr. Block, or so forth. But I felt it was much more useful and more interesting to focus on one specific example from the I.W.W. over the course of 10–15 pages where I could explain the history and have room to debate the tactics.

So for the IWW chapter I detailed the Paterson Pageant of 1913 – a one-night pageant at Madison Square Garden where over 1,000 striking workers re-enacted the Paterson silk workers strike during the strike itself. This pageant was so controversial because the strike fell apart shortly after the performance and some blamed the use of art for its demise. (Read an excerpt from this chapter HERE)

I definitely noticed that there was more of a focus in your book on the difficulties of doing this kind of work, whereas most books on the subject are pretty celebratory. What led to that decision?

To me, the most interesting chapters are those in which the art backfired somewhat, or where it was complicated. I think a book that’s simply celebratory is dishonest, and doesn’t do justice to the realities of social movements. Movements rarely are defined as a series of victories.

My book is best understood as a series of tactics — ones that were exceedingly complicated. Again the Patterson Pageant is a good example. 25,000 silk workers, mostly recent immigrants from Eastern Europe, went on strike in Patterson, New Jersey just south of New York City. The IWW came in as strike organizers, and they made the decision to bring in avant-garde, middle-to-upper class artists from Greenwich Village to help publicize the strike. What became complicated was the class dynamics. People like John Reed, a recent Harvard graduate who directed the Pageant and later became a famous journalist, could act in solidarity with the striking workers. But he had less at stake if the strike succeeded or not. His livelihood was not on the line. The situation was much different for the recent immigrant on strike whose family was at near starvation.

That said, I think the chapter was about solidarity. Solidarity is of course positive, but the tactics have to be well thought out. Studying past examples of solidarity across class lines is instructive to solidarity efforts today. We can learn from the tactics of the past and hopefully duplicate what’s successful, or at least have a sharper sense of critique about what not to do.

I definitely appreciated the focus on complexity and contradiction. I also noticed that, compared to other histories of political art, this one strayed farther away from professional artists and gallery artists, and brought in types of art that other people may not even have thought to include. For example, you start right off the bat with wampum belts.

My decision from the onset was to focus on the art that happens outside of the art world – a parallel art history to the standard version. Of course, there is crossover, but I tried to veer away from writing about artists whose work was rooted in a gallery or a museum. Instead, I wrote about artists like Emory Douglas from the Black Panther Party, or the photographers in SNCC, whose work at the time was rooted in a movement. I was arguing that the art world is too isolated, that it reaches too small of audience to have the same level of impact that movement culture does. I wasn’t dismissing museums and galleries. The ideas put forth in the those spaces are significant, but the audience and the level of collaboration differs.

A good example today would be to differentiate between a museum show about climate change versus artists working directly within environmental groups and using creative resistance tactics to block tar sands trains and pipelines. I find the later example to be a form of activist art, whereas the artist showing in the museum is political art. Both approaches are needed, but my book was focused on a history of activist art.

In terms of individuals or groups out there today, who do you think is doing particularly good work around art and social movements?

Coming up with a list is so difficult because there’s so much good work happening. That was part of my struggle with the book and why I decided not to follow a survey route. I didn’t want it to feel like a “who’s who” of important artists.

Well, who are a few that you personally are into?

Favianna Rodriguez is doing really important work on migrant workers rights. I am also really impressed by Iraq Veterans Against the War, a group that has really harnessed art and cultural resistance better than most out there. I think the People’s Climate March was really incredible to see, not just because of how much art was in it, but because of the leadership role that artists took in framing the march.

Across the pond, Liberate TATE is doing amazing stuff, interventions into the Tate Modern where they are bringing to light the corporate sponsorship of the museum and the need to divest from the fossil fuel industry. The Illuminator Project, the Overpass Light Brigade…the list goes on and on. I admire the work where artists are directly aligned with, and part of, social justice movements. Not just on the outside adding commentary.

Even just listing artists to you, you can see my hesitation with surveys because you inherently miss a lot of important work. That’s why, in my book, I wanted to choose one specific example for each decade throughout American history, and to really lay out how the artists interfaced with a particular movement.

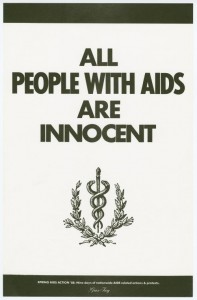

I wanted to study what worked and what did not. The model that I often look to is ACT UP, and specifically Gran Fury. Gran Fury is so significant because were 10 to 12 designers and they acted as an affinity group within the larger framework of ACT UP. This was so brilliant because it allowed them and other affinity groups to work towards a common goal, but it didn’t bog down the artists to have to get consensus or to explain their process to a larger group of 500-700 activists. That would have diluted the process and prevented artists from working quickly, which is needed when the goal is to disseminate graphics fast.

In the process of writing A People’s Art History, what surprised you? How have your ideas about art and social justice changed through this project?

Similar to when I first read Howard Zinn’s People’s History, I was surprised by how much I didn’t know. Just the pure volume of artists and activists engaged in these forms of creative resistance. I was also surprised by the recycling of tactics. Many of the conversations that artists were having in the 1920s and 1930s are conversations that resurface today: critiques of the gallery system, the economic issues of how artists survive, the need for more public art, the need to harness art to social justice movements. Those conversations happened at the American Artists’ Congress in 1936 and through the Artists’ Union in the 1930s, and among 1960s groups like the Art Workers’ Coalition and Guerrilla Art Action Group. Recently you see groups coming out of Occupy Wall Street like Occupy Museums making the same calls.

In Justseeds I work in the realm of producing graphics for movements, and to me it was really interesting to read about other artists going back through American history that were doing the exact same thing. Their technology may differ, and the way the work is disseminated may differ, but the spirit behind the work is similar. There are a lot of parallels between the past and the recent present. I wrote about the Workers Film and Photo League (F&PL) in the late 1920s and early 1930s. They remind me a lot of the “Become the Media” movement that emerged out of the Seattle WTO protests in 1999. There is a recycling of tactics because people are responding to similar calls for justice. And there is a lot to learn about from this history if we carefully study and critique it. I wouldn’t say that my book is a hidden history, but the material in it is certainly not common knowledge to many of us.

Its certainly not what you run across in your art history classes

No it was not.

Thank you for your time, and for the book.