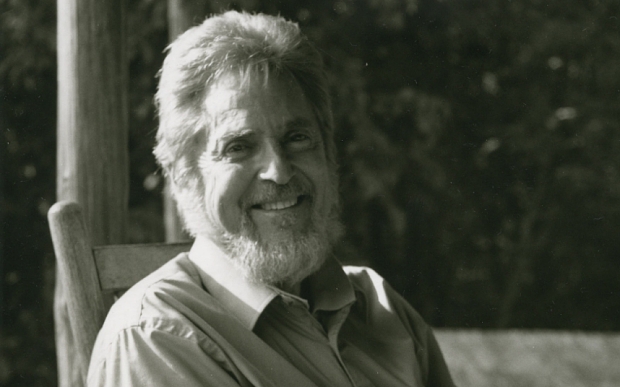

This past month we lost one of the great cultural organizers of our time. Guy Carawan passed away on May 2 at the age of 87, closing out a life dedicated to music, justice, and the celebration of folk culture. As music director at the Highlander Folk School, he was a gentle hand guiding the spread of the freedom songs. With his wife Candie, and later his two children, he supported social justice struggles in the US and around the world, while documenting the rich diversity of folk and indigenous music.

Carawan began his career as a musician in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a transitional time for US folk music. The first wave of the folk music revival was dying down, battered by McCarthyism and the Red Scare, while the seeds of the second wave were being sown. As a student at Occidental College and UCLA, where he studied sociology, Carawan became involved with the progressive folk music community in LA. He later moved to New York City to join the Greenwich Village folk scene. In the summer of 1953 he famously toured the south with singers Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and Frank Hamilton, listening to folk and country musicians throughout Appalachia — a trip memorialized in Ramblin’ Jack’s song 912 Greens.

It was while on this trip that Carawan first visited the Highlander Folk School (now the Highlander Research and Education Center). Since its founding in 1932, Highlander has been a focal point of cultural organizing, due in large part to the efforts of Zilphia Horton, the Center’s first music director. Horton believed strongly in the importance of music, particularly group singing, which she saw as a way to forge group solidarity, foster cultural pride, keep indigenous leaders connected to the masses, transmit stories and ideological messages, and inspire activism. She worked to integrate singing into all aspects of the Highlander curriculum. Horton died in a tragic accident in 1956.

In 1959, Carawan took over as the Highlander music director and continued Horton’s work. While the Center’s early efforts had largely been in support of radical union organizing, by 1959 Highlander had become a key training ground for civil rights organizers, including many well-know figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Highlander served as a launching pad for the Citizen Schools, as well as the freedom songs that would become the sound track for the movement.

Like Horton, Carawan believed that music could bridge racial and cultural divides. By combining aspects of Black spirituals and white folk music, Carawan hoped to help integrate the civil rights movement. He is most famously noted for his role in adapting and spreading the anthem “We Shall Overcome” throughout the movement. A snapshot of his work is captured in this quote by Reverend C. T. Vivian, a close colleague of MLK:

I don’t think we had ever thought of spirituals as movement material. When the movement came up, we couldn’t apply them. The concept has to be there. It wasn’t just to have the music but to take the music out of our past and apply it to the new situation, to change it so it really fit.…. The first time I remember any change in our songs was when Guy came down from Highlander. Here he was with this guitar and tall thin frame, leaning forward and patting that foot. I remember James Bevel and I looked across at each other and smiled. Guy had taken this song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd” — I didn’t know the song, but he gave some background on it and boom — that began to make sense. And, little by little, spiritual after spiritual began to appear with new words and changes: “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, Hold On” or “I’m Going to Sit at the Welcome Table.” Once we had seen it done, we could begin to do it. (qufoted in Sing For Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs, 1990.)

This last statement, “once we had seen it done, we could begin to do it,” speaks beautifully to Carawan’s style of cultural organizing, which was humble, behind-the-scenes, and focused on empowering others as leaders. Over time, Carawan came to the decision that others were more capable of carrying the torch of the freedom songs. He turned his attention to teaching young African American singers, and to documenting the music and story of the civil rights movement.

As Highlander shifted its focus in the 1970s to Appalachia, Guy and his wife Candie, who he met at Highlander, helped to support social and environmental justice issues in the area, including the black lung movement. Along with their two children, they have worked to document and celebrate the music and culture of Appalachia, the Sea Islands, and other groups, inspiring artists and cultural workers along the way. Their books include, Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life? The People of Johns Island, South Carolina — their faces, their words and their songs, and Freedom is a Constant Struggle Songs of The Freedom Movement, with Documentary Photographs.

In their online tribute to Caraway, the Highlander Center wrote the following about their long-time colleague and friend.

Groups that visit Highlander know that here on the hill we still sing. We stand in that circle of rocking chairs, cross our arms, link our hands, and sing the songs that so many have sung before us – and at the same time we learn and teach new songs from new communities struggling for justice – sharing old and new alike in an ongoing chain of support and inspiration. This is Guy’s legacy. We will continue singing, and we will think of him when we do.

Further reading that informed this post:

Guy and Candie Carawan: A Personal Story through Sight and Sound

The Culture War in the Civil Rights Movement, by Joe Street

Guy Carawan, by Ellen Harold and Peter Stone, at Cultural Equity

Featured photograph by Heather Carawan, taken from CC Wikipedia