“The decision to act heroically is a choice

that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in time.”

“The decision to act heroically is a choice

that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in time.”

– Dr. Philip Zimbardo

This past week DC comics — home of Superman, Wonder Woman, and Batman — began rebooting 52 titles, starting them at #1 and rewriting decades of complicated, often contradictory, fictional history. While this is a rather cheap ploy to excite readers and lift up declining sales, I’d like to use this moment in comic publication history to muse on the power of superhero myths, and the usefulness of these myths for social justice organizing.

As I discussed in a previous post, one of the ways that power is wielded in our society is through story and myth. Myths like the American Dream, or the Thanksgiving creation story, help to uphold the status quo as good or at least natural. At the same time, myths like the story of Rosa Parks help us to envision ways that individuals can change unjust systems. While the term “myth” is often used to refer to something that is not true, I’m using it here quite differently. A myth is simply a story that is retold time and again, and helps us to understand something about the way things are, and how the world works. The “truth” of a myth lies not so much in its literal truth (though that varies) but in its ability to guide our lives in useful and positive ways.

One set of myths that are as alive as ever in our society, marked by a current deluge of movies, are those surrounding the superhero. U.S. superheroes are a modern extension of the eons-old hero mythologies most famously outlined by Joseph Campbell — though they have arguably been adapted in peculiarly American ways. Superhero tales, introduced in their current form by Superman in 1932, offer us models of morality, and of how “wrongs” are made “right.”

On a literal level, traditional superheroes offer us a pretty weak model for how to improve the world. They generally function in stark binaries of good and evil, and their solution is almost always physical violence. There is no real accountability — people just have to trust that they will do “good.” They often work alone, and are seen to stand apart from the rest of humanity. And when they take on social issues like crime, it is generally by punching and arresting people in alleys, rather than addressing any of the systemic roots of the problem. (This is to say nothing about the underlying racism, sexism, and heterosexism rampant in the superhero genre, but that is a story for another time.)

Some of the best comic book authors have explored these limitations. In one of my favorite examples — Superman: Peace on Earth — Superman takes on world hunger. In an effort to inspire more equal distribution of food reserves, based on the charity model, Superman announces to the UN that he will spend one full day carrying massive amounts of food from rich countries to poor ones suffering from famine. It starts out all right — people are happy to receive free food. But problems begin piling up. In one country the food he brings simply isn’t enough. In another, nobody trusts the food and so it’s left for the rats. In another, a military dictatorship is more than happy to take the food, with no intention of sharing it across the country. Finally, seeing Superman as a threat to national sovereignty, one country fires a missile and blows him out of the sky. In the end it is a failure, both for this particular mission, and for the superhero model of change. (At the end Clark Kent, who after all grew up on a farm, teaches young people to grow their own food. Also not a systemic solution to world hunger, but a human-sized occupation that can have its own empowering results.)

It may be that this model of the individual hero — though not originating with superheroes — harms attempts to organize for social change, as we rewrite our lives to fit our myths. In many ways the civil rights movement is taught as something of a superhero myth, with Martin Luther King as Superman. This has the danger in the moment of discouraging the development of other leaders, leaving the movement in trouble when tragedy takes our hero from us. In the longer-term, it can leave us, as they say, “Waiting for Superman” rather than taking action to change things now. Would we be better off with more focus on stories that highlight the less hierarchical, collective work that formed the base of the civil rights movement? The work of SNCC and the Freedom Schools for instance?

Rosa Parks is a perfect example of this. Her myth is one of a single, principled individual taking a stand, and igniting a movement. This is for sure an inspiring story. But would it be more helpful if the myth clung closer to reality — the story not of an individual making a spur-of-the-moment choice but a trained and committed organizer working with many others to plan out an incredibly successful action?

But I am not ready to throw out superheroes all together. Perhaps it’s simply because I like reading comic books. Or perhaps it’s because I didn’t grow up on Superman so much as the X-Men. While the X-Men fall into some of the traps outlined above, they are far from the shiny, American Way Superman, or the rich, unstable renegade Batman. They are outcasts, facing constant discrimination. They have powers, but these powers are often odd and sometimes debilitating. X-Men generally can only succeed when they come together as a team, uniting their diverse skills. And they are flawed in clear and not-so-clear ways.

So to me, superheroes continue to be an inspiration, and a set of myths I come back to. One reason is because of their unabashed celebration of power (or “powers”). As Alinsky wrote decades ago, if we want to change systems we cannot shy away from the idea of “power.” Power does not equal oppression. It is the unequal distribution of power that leads to oppression. Power, in organizing and in superheroics, is where change comes from — whether power from collective social capital, or a radioactive spider.

I personally like to stress the collective aspects of superhero myths, since I believe collective action is the only route to systemic change. (After all, superheroes are forever forming “leagues.”) But we should not be too quick to discount the importance of the individual hero. My partner recently shared with me the writing of Philip Zimbardo, who conducted the famous Stanford Prison Experiment in which students pretended to be guards and prisoners. It got so brutal that it had to be shut down after six days — and that was already too long. Zambardo writes about the Lucifer Effect, the way that good people can end up carrying out evil acts through obedience to authority or passive observation. His solution? The celebration of heroism, of the individuals who resist inertia and choose to act differently. He has founded the Heroic Imagination Project whose mission is to “encourage and empower individuals to take heroic action during crucial moments in their lives. We prepare them to act with integrity, compassion, and moral courage, heightened by an understanding of the power of situational forces.”

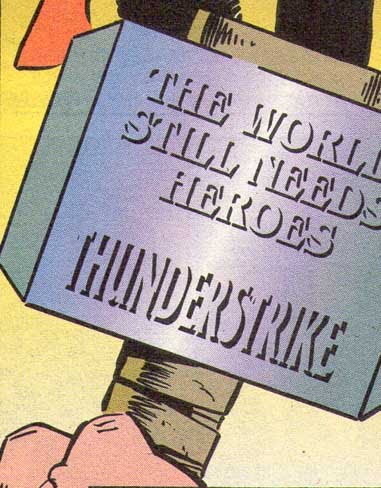

Zambardo’s message could be summed up by the inscription Eric Masterson found on the hammer created for him by Odin, after he stopped being the superhero Thor. Despite their problems and limitations, despite their mixed history of success, and despite all the critiques offered above, “The World Still Needs Heroes.”

4 Comments

Your post reminded me of a recent npr.com Monkey See blog post by Glen Weldon about the new multi-racial Spiderman, Miles Morales, suggesting that a little more diversity among comic book characters might change the “multiverse.”

http://www.npr.org/blogs/monkeysee/2011/08/03/138948576/meet-your-friendly-neighborhood-well-community-based-anyway-spider-man

Thanks for the link. Superhero comics tend to be behind the times in increasing various forms of diversity. The other character I’m excited about, who has come onto the scene in recent years (brought back by one of my favorite authors, Grant Morrison) is the new Batwoman, who is the highest-profile gay character in comics. She’s got her own book coming out, by fabulous artist JH WIlliams III. Check out this article from the Advocate: http://www.advocate.com/Arts_and_Entertainment/Features/Batwoman_The_Allure_of_the_Lesbian_Caped_Crusader/

I thought this was a funny and pithy piece on why Rick Perry should admire Superman that my cousin posted, so I’m reposting it here.

Hi Paul! This is such a great post! And thanks for the wedding wishes. 🙂